Contributed by Jay Follis, Gilmore Car Museum, Curator

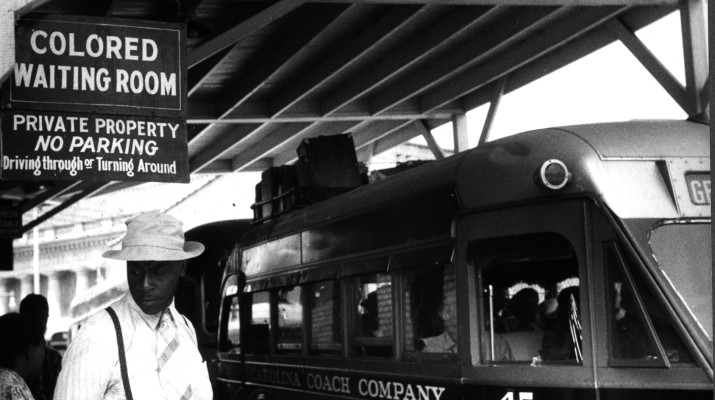

Header image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

MUSEUM EXHIBIT RECALLS AN ERA WHEN “GREEN BOOK” HELPED EASE THE WAY FOR AFRICAN-AMERICAN TRAVELERS

- “The Negro Travelers’ Green Book” was compiled by a New York City postman with help from postal carriers around the country

- Black travelers faced “whites only” lodging, restaurants, even gas stations

- Rockefeller’s Esso brand sold gas, franchises to African-Americans

Hickory Corners (MICH) – In the spring of 1946, Jack Roosevelt Robinson, a former multi-sport standout at UCLA and a U.S. Army veteran, and his bride of two weeks Rachel, were flying from Los Angeles to Florida for baseball’s spring training season. Yet twice along the route, they were bumped from flights so their seats could be occupied by passengers with white skin. During a stopover in New Orleans, they were not allowed to eat in the “whites only” airport restaurant. After arriving in Florida, the driver ordered them— yes—to the back of the bus.

The Robinsons, Jackie — soon to wear the Brooklyn Dodgers’ No. 42 on his back — and Rachel, were not alone. African-Americans faced discrimination in many aspects of life, including lodging, dining, when trying to find a drinking fountain or a restroom or even when trying to buy gasoline for their cars.

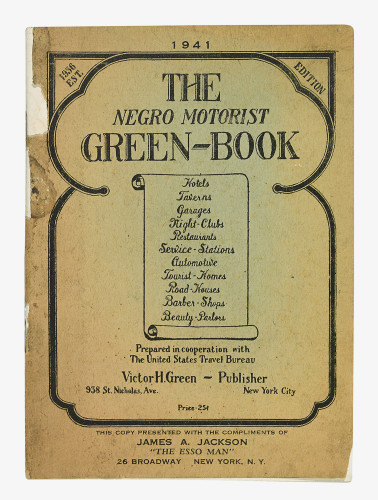

To ease their way, Victor Hugo Green published “The Negro Travelers’ Green Book” with a listing of places — some commercial, some private homes — where dark-skinned people could stay and eat, where they could buy gas and even which towns to avoid for their own safety. Green, an African-American mail carrier, was outlived by his annual book. He started it in the mid-1930s and his company kept it going until the passage of civil rights legislation in the 1960s.

No doubt many people first learned of the Green Book in August 2015 when The New York Times did a feature story about the book, or seeing previews for the upcoming film, Green Book. However, visitors to the Gilmore Car Museum in Hickory Corners, Michigan have been exposed to the book and its role on black travel since late in 2014 when the museum opened its Green Book exhibit.[/caption]

David Lyon, Automotive historian, and author, recently pointed out that Gilmore’s display is likely, “the only Green Book exhibit at an automobile museum in this country, and perhaps the world.”

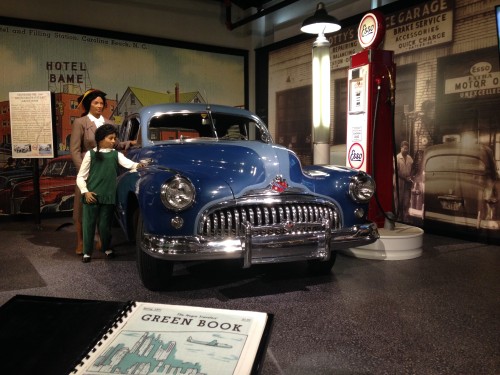

The exhibit includes the life-like museum figures of a mother and daughter and a two-tone 1948 Buick sedan parked at an Esso filing station. Information panels provide details, a large video plays interviews with African-Americans who experienced discrimination while traveling and a copy of the Spring 1956 edition of a Green Book is there for museum visitors to examine.

“It’s a story that had been pretty much forgotten,” said museum curator Jay Follis. “We’ve had a tremendous number of people seeing it and saying, ‘I’ve never heard of this’.”

Victor Hugo Green was a native of Hackensack, New Jersey, and a mail carrier in New York City. His wife was from Virginia and as they traveled to visit family, they encountered Jim Crow restrictions. A Jewish friend showed Green a guidebook used to avoid “gentile-only” establishments and Green started his Green Book. He enlisted mail carriers across the country to help him compile and update the listings.

There’s a reason the gas station in the Gilmore museum diorama has an Esso pump. Esso was a brand of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company.

Follis explained that Esso had a program to help African-Americans buy and operate its service stations. Esso also provided offices and support for the staff that helped Green produce and publish his guides.

Rockefeller was married to Laura “Cettie” Spelman, a daughter of abolitionists. The Spelman home had been part of the Underground Railroad. Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary, founded late in the 19th century to educate young black women, would become Spelman Seminary and later Spelman College in honor of Cettie’s family’s work and contributions.

The Green Book diorama is one of two that are a permanent part of the Gilmore museum’s display. The other — The American Exodus — focuses on the hardships of the Depression-era migration from the Midwestern “Dust Bowl” to the promised-land on the West Coast. Both have had profound impacts on guests and are regularly used by the Museum’s education team.

The Gilmore Car Museum—North America’s Largest Auto Museum—is located midway between Chicago and Detroit. In addition to nearly 400 vehicles, many of them housed in historic buildings and re-created automobile dealerships, its 90-acre campus includes a vintage gasoline station and authentic 1941 Blue Moon Diner that serves lunch daily. The museum is open daily except for Easter, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day.

To learn more about the Gilmore Car Museum visit:

To learn more about the Gilmore Car Museum visit:

www.GilmoreCarMuseum.org or call the Museum at 269-671-5089.